Blockchains and scalability

Published:

History and Background

The history of exchange and currency is a tale that predates civilization itself. This staunchly human story transcends written history and is a focal point for historians, archaeologists, and economists alike. What is known, however, is the importance "money" has had on societal development.

As an abstraction, the ebb and flow of an economy can be famously characterized into Adam Smith's dynamic system. This concept encompasses his famous phrase the invisible hand, in that the market will tend towards homeostasis. Today, modern economists revisit these economic theories with increasingly liberal lenses. For example, Dr. Popescu of The Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies argues that the "dynamic equilibrium" that characterizes economic activity fulfills the requirements for a living whole [1]. Regardless of the classification, it is relevant to acknowledge the responsive nature of economic activity.

In 2007 the United States housing bubble burst as homeowners began to default on their subprime mortgages. These mortgage-related economic losses strained the United States' financial market and snowballed the US economy into a recession. This recession quickly became a global issue as several major investment banks collapsed in response to trickling financial concerns. The final impact of this economic crisis resulted in the largest global recession since the Great Depression. Throughout this economic withdraw, a novel trading system emerged independent of traditional centralized financial system.

In response to the financial crisis and economic uncertainty, other alternatives to the dwindling fiat currencies were explored in the late 2000s. Historically, gold, silver, and other precious metals have been the discrete investment option against economic crisis. The relationship between precious metals and the stock market is typically inverse [2]. After the economic collapse in 2008, gold prices increased over $1,000 per troy ounce. At the same time, the increase in consumer technology began to highlight the possibility of digital alternatives to fiat currency.

In late 2007, Satoshi Nakamoto published the paper "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System." This paper revisited the previously theoretical idea of a cryptographically-produced currency. Dating back to 1983, there were primitive and incomplete attempts to develop "virtual" currencies such as eCash and DigiCash [3]. Unlike these previous developments, Nakamoto outlined the first concept of blockchain technology in a decentralized digital system. Nakamoto's whitepaper summarizes this system as -

"The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power" [4]

The decentralized system allowed for the transaction of electronic cash (bitcoin) without the oversight of a financial institution, hence the decentralized moniker. The decentralized aspect of bitcoin in combination with its ease of use, portability, and finite supply characterized itself as a unique alternative to fiat currency. By 2009, bitcoin was released to the public as a functional substitute for centralized currencies.

What are cryptocurrencies?

At its root, a cryptocurrency is an entirely virtual tender that is secured by a form of cryptography. Cryptocurrencies are often distributed on a decentralized ledger known as a blockchain to manage and record transactions (nerd wallet). Cryptocurrencies are designed to act as method of payment to be exchanged for goods and services. In principle, this concept is no different from using tokens at an arcade or chips at a casino. Either way, the transaction substitutes real world currency to obtain / access a good or service.

As of November 26, 2021, there are over 14,800 individual crypto currencies [5]. These currencies are actively traded on over 400 global exchanges with a total market capitalization (aggerated value of all existing currency) of nearly 2.5 trillion USD [5]. The most popular cryptocurrency, bitcoin, is estimated around 1.1 trillion USD [5]. Eight of the most popular cryptocurrencies along with their estimated market capitalization is shown below [5].

| Cryptocurrency | Market Capitalization |

|---|---|

| Bitcoin | $1.1 trillion |

| Ethereum | $521 billion |

| Binance Coin | $94 billion |

| Tether | $73 billion |

| Solana | $62 billion |

| Cardano | $54 billion |

| XRP | $38 billion |

Double Spending and Decentralization

Before defining the blockchain, it is essential to first understand why the blockchain is necessary within the bitcoin network. "Double-spending" is an age-old issue in remote and digital transactions. As the name suggests, double-spending is the error in which the same currency is spent twice. In direct and physical transactions, this issue is impossible. For example, envision a coffee shop that only accepts cash. If an individual opts to pay for a $1 coffee in cash, the cashier takes the $1 bill and places it in the cash register. Once the dollar is physically removed from the customer's hand and placed in the register, the customer can't re-spend that dollar. The dollar is and will be in the coffee shop's possession until it is physically spent/moved elsewhere.

Digital transactions complicate this exchange. In centralized systems, banks and financial institutions safeguard against double-spending by mediating the transaction of currency. If the same customer in the previous example wished to buy a coffee using the centralized system (such as a debit card), they would first deposit $1 into their bank account. Once the individual swipes their debit card to purchases the coffee, the coffee shop trusts the bank in remotely transferring $1 to the shop's bank. Here, both the customer and the coffee shop acts on mutual established trust with the bank.

Proponents against the centralized system object to several fundamental aspects of the trust based architecture. Componently, the centralized system is built on a single point failure. If the established bank or financial institution collapses, who can verify the transaction?

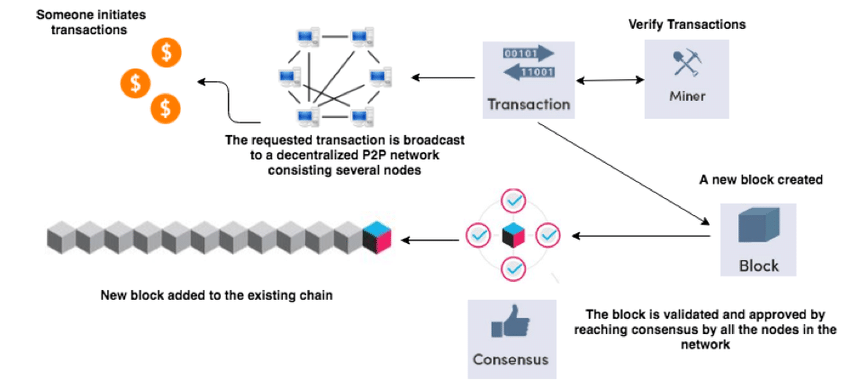

The ingenuity of the blockchain roots in its solution to the double-spending problem. A blockchain is defined as "digital, decentralized, and distributed ledger in which transactions are logged and added in chronological order with the goal of creating permanent and tamper-proof records" [6]. In the case of the coffee shop, the customer would first acquire $1 worth of bitcoin. They would then send the bitcoin to the coffee shop's bitcoin address. This transaction would be confirmed by the bitcoin network (miners) and validated in the next block. The blockchain timestamps this transaction and then broadcasts its validity to all nodes in the network [4]. The transaction is then mathematically related to all the previous blocks so its history is impossible to forge.

Figure 1: blockchain network [7]

Block Elements

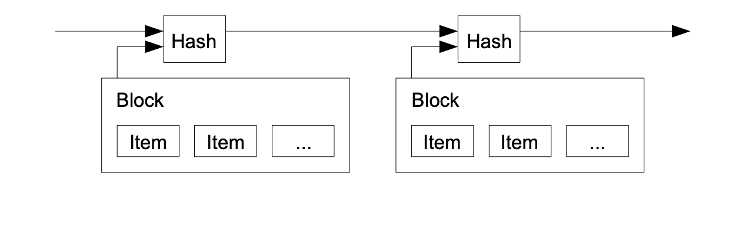

The block is the most fundamental element of the blockchain. As the name implies, a blockchain is merely a "chain" of connected "blocks." Similar to a linked list, blocks are strung together though a reference to their previous block. One committed to the chain, the data becomes immutable from the stack of blocks before it, and thus permanently linked to all previous transactions [8].

Each block represents of a node containing a block header and a block body. In the case of cryptocurrencies, the block body contains a collection of recent transaction information. The block header contains a unique hash that differentiates the current block every other block on the network [9].

One of the most important aspects of blockchain technology is the implied support of a decentralized and trust-less leger. While centralized "private" blockchains do exist for specific use cases, the majority of blockchains are public and thus decentralized. In reference to blockchain "authority" Vitalik Buterin (a co-creator of Ethereum claims) -

"Blockchains are politically decentralized (no one controls them) and architecturally decentralized (no infrastructural central point of failure) but they are logically centralized (there is one commonly agreed state and the system behaves like a single computer)" [11].

Public blockchains allow all participants to contribute new blocks. Every time a new block is added to the blockchain it is broadcasted to all other participants on the blockchain [9]. Assuming the block is valid according to its signature, hash, and payload, it is permanently solidified in the blockchain.

Consistency on Blockchains

Maintaining consensus along the blockchain is an important to ensure only one node adds to the chain at a time. This responsibility is upheld by the blockchain's consensus protocol. There are currently many different consensus protocols but most can be categorized into either proof-based or vote based consensus protocols. Proof-based consensus protocols require participating entities to disclose a tangible amount of work or resource expenditure. Based on the algorithm, the most "qualified" node will append the block [12]. The two most popular proof-based consensus algorithms are proof of work (PoW) and proof of stake (PoS). On the other hand, Vote-based consensus protocols exchange verification information collectively before determining the contributing node [12].

Proof of Work:

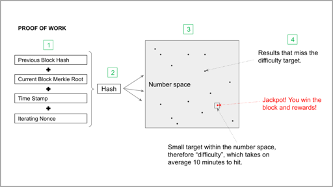

The most widely adopted consensus protocol currently is proof of work [13]. PoW protocols are used in some of the most popular cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Dogecoin. In PoW, individual network participants compete for the right to add new blocks to the blockchain though computational power [9]. The computational power is used to solve a hash puzzle who's solution is included in the next block. This process highly intensive and probabilistic. The odds of computing the "target" result is very low (depending on computational power), but the rewards can be substantial. Due to this effort vs reward dynamic, participants in PoW blockchains are aptly named "miners". The reward for completing the mining race is currently 12.5 bitcoin or nearly $700,000 in 2021 [5].

Figure 2: visualization of Proof of Work [14]

Proof of Stake:

Proof of State is debatably the next most popular consensus protocol. Unlike PoW, PoS overcomes the raw computational needs and incentivizes the investment of the given cryptocurrency. In a PoS system, participants "stake" a given amount of cryptocurrency and are rewarded with the chance of mining / validating block transactions. If a participant were to contribute 10% of minted currency to a stake, the probability of mining the next block is 10%.While this is protocol is still emerging, popular currencies such as Cardano and the up-coming Ethereum 2.0 have adopted PoS [12].

Blockchain Scalability

Theoretically, the size of the blockchain is unlimited. As blocks are continuously added to the blockchain, the size will grow linearly. The rate a blockchain grows is dependent on the block size (size of each block) and the block interval (how often a block is added). Bitcoin currently has a block size of 1MB and a block interval of 10 minutes on average [4].

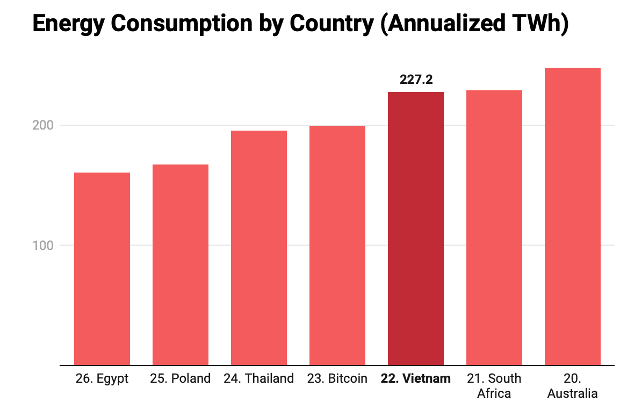

There are notable objections to the scalability of the blockchain networks. Environmentally, it can be argued that the energy requirement to support a large scale blockchain is unstainable. As of 2021, bitcoin mining consumes nearly 91 terawatt-hours of electricity [15]. In perspective, this consumption trumps the annual energy expenditure of most countries and accounts for over 0.5% of electricity consumption worldwide [15]. If bitcoin was a country it's energy consumption would rank globally below

Figure 3: bitcoin ranked as a country [16]

In terms of ecological footprint, blockchain technology bears an impressive burden on global CO2 emissions. Typically, participation in proof-of-work structured blockchains is called "mining." Miners in PoW featured blockchains are in constant competition to contribute the next bitcoin block. The CO2 implications of this race account for 272 tones of CO2 annually [16]. In perspective, this is output is over 10x the annual gold (metal) mining footprint.

The architecture of bitcoin is not only energy demanding but extremely limited in transaction processing. Blockchains inherently suffer from scalability issues as transactions pile into the network. In its primordial state, bitcoin had no issue supporting transactions on the network blockchain. As users and transactions grew exponentially over time, trusted third parties were added to merely mitigate the issue [17].

Transaction throughput has highlighted the limitations of the blockchain network as users exponentially increase. As the first and most widely used blockchain, bitcoin is often referenced as a case study to accentuate the underling scalability issues. A hard limitation on the bitcoin blockchain is the block interval of around 10 minutes and the block size of around 1 MB [4]. With this design consideration, it is estimated that the highest transaction throughput on the native bitcoin network is 7 transactions per second [17]. In comparison, the Visa network can support over 65,000 transactions per second [18]. If all 7.7 billion people on the planet made a single bitcoin transaction, it would take over 35 years for the last transfer to clear [18].

Ideally, the clear answer to this problem would be increasing the hard limitations surrounding the block interval and block size. While this adjustment has been proposed and implemented in other cryptocurrencies, the consensus hardware implications could endanger the envisioned decentralized system [17]. Currently, the bitcoin blockchain grows at a maximum of 1 gigabyte a week. To double the block size would increase the blockchain 2 gigabytes a week, to quadruple the block size would increase the blockchain 4 gigabytes a week, and so on. Likewise, increasing the block interval would have a similar effect. An accommodating node storage upgrade would hardly concern a centralized or institutional system. In a decentralized system however, a rapid node storage upgrade could financially prohibit many miners from participating in the blockchain network [17].

Outside of the performance bottleneck, there is a physical capacity concern with large blockchains. The bitcoin network grows linearly as new blocks are added to the blockchain. Even considering Moore's law, the sheer size of a continuous blockchain could limit the entrance of new participants in the network. A current concern with bitcoin is the developing bootstrap time [19]. In order for new nodes to participate in the bitcoin network, initial configurations along with the entirety of the blockchain must be collected. As the blockchain history becomes exuberantly large, one can envision the hardware strain this would relay on smaller network participants. To mitigate this concern in the future, sharing techniques and compression methods have been proposed to solve the blockchain capacity problem [17].

Scalability Solutions

To alleviate scalability shortcomings on the bitcoin blockchain, novel "on-chain" and "non-chain" solutions dissipate the stress on the native network. Bitcoin-Cash is an example of a "on-chain" solution to scale the original bitcoin blockchain for everyday use. Created as a hard fork in 2017, Bitcoin-Cash accommodates more transactions per block by increasing its block size to 8MB or 8X larger than bitcoin's original 1MB [20]. An example of a "non-chain" scalability solution is seen in the Lightning Network. The Lightning Network essentially creates a temporary off-chain trading channel to carry out low-latency transactions [17]. At the expense of marginal security and success rate, users can quickly interact off chain.

The scalability of blockchain technology continues to be an area of continued research and development. Blockchains must consider factors of security, decentralization, and ecological concerns while they inevitably grow in size.

Cryptology and Hashing

The cornerstone of blockchain technology is cryptography. Hashing algorithms are used to create the links between blocks and to verify proof-of-work consensus algorithms. Key cryptography is used to identify and prove ownership of digital assets. Digital signature schemes are used to verify the conditions and authenticity of transactions. Without cryptography, a "decentralized" network would be unsecure and difficult to manage.

To formalize agreements such as contracts, transactions, and treaties, nonfungible signatures must be used to certify authenticity. In the digital world, cryptography is used to guarantee that signatures are authentic and valid. The bitcoin network currently uses the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) to identify users [20]. This algorithm is used to generate a public-private key pair that is difficult to forge and easy to verify.

A hash is a cryptographic representation of a data. A hash function is used to transform an input into a unique and characteristic output. Even a small change to the input will result in drastically different outputs. In Nakamoto's original bitcoin whitepaper, hashing is used to link each block in the blockchain. This secures the block chain as each block's hash is affected by the previous hash value [4].

Figure 4: Nakamoto's blockchain link

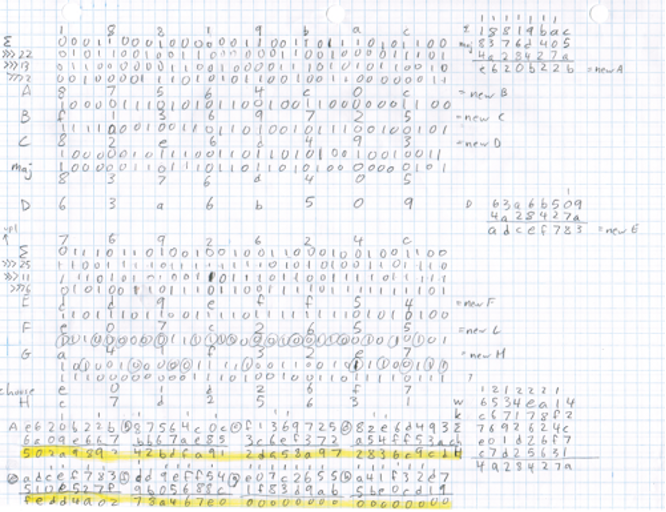

Bitcoin mining is essentially conducted by running SHA-256 hashing functions in series. The miner's objective is to solve a SHA-256 "puzzle" before other miners for the right to append the next block. The puzzle solution is a hash value for the block header that starts with a known number of zeros [20]. To increase the difficulty and thereby increase the security of the blockchain, the bitcoin network employs the SHA-256 functions twice known as double-SHA-256. A hand written example of SHA-256 hashing a bitcoin block is shown below [21]. The final hash is highlighted in yellow.

Figure 5: The hash result is highlighted in yellow, showing a successfully-mined bitcoin block

Conclusion and Further Research

To date, interest in blockchain technology has increased tremendously. Blockchain architecture has been implemented in countless consumer, technical, business, and legal design options [8]. Over thirty countries are investing in blockchain projects and nearly 80% of banks predict to incorporate blockchain related technology in the future [8]. Since Bitcoin's introduction in 2009, blockchain technology has expanded globally. A testament to human innovation and cryptology, the blockchain has even been labeled as most influential invention of our decade [22]. Further research will continue to innovate more sustainable and ecologically justifiable decentralized options.

WORKS CITED

C. Popescu, "The Health of the Economy as a Living Organism," Theoretical and Applied Economics, vol. XVII, no. 2010, 2010.

Online, "How gold fares as investment in economic crisis?," The Financial Express, 06-May-2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.financialexpress.com/money/how-gold-fares-as-investment-in-economic-crisis/1950016/. [Accessed: 2021].

Davies, "A short history of Cryptocurrencies," Davies. [Online]. Available: https://daviescoin.io/blog/a-short-history-of-cryptocurrencies. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

S. Nakamoto, "Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system," 2008. [Online]. Available: http://nakamotoinstitute.org/bitcoin/.

"Cryptocurrency Prices, Charts and Market Capitalizations." CoinMarketCap, coinmarketcap.com/.

H. Treiblmaier, "The impact of the blockchain on the supply chain: A theory-based research framework and a call for action," Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 545–559, 2018.

A. Monrat, O. Schelén and K. Andersson, "A Survey of Blockchain From the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities," in IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 117134-117151, 2019, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2936094.

P. Tasca and C. J. Tessone, "Taxonomy of blockchain technologies. principles of identification and classification," arXiv.org, 16-Apr-2018. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.04872. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

K. Raj. Foundations of Blockchain: The Pathway to Cryptocurrencies and Decentralized Blockchain Applications. Packt Publishing, 2019.

F. Knirsch, A. Unterweger, and D. Engel, "Implementing a blockchain from scratch: Why, how, and what we learned," EURASIP Journal on Information Security, vol. 2019, no. 1, 2019.

V. Buterin, "The meaning of decentralization," Medium, 06-Feb-2017. [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/@VitalikButerin/the-meaning-of-decentralization-a0c92b76a274. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

T. Nguyen and K. Kim, "A Survey about Consensus Algorithms Used in Blockchain," Journal of Information Processing Systems, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2018.

N. R. Mosteanu and A. Faccia, "Fintech Frontiers in Quantum Computing, Fractals, and Blockchain Distributed Ledger: Paradigm Shifts and Open Innovation," Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 19, Jan. 2021.

D. McIntyre, "Why proof of work based Nakamoto Consensus is secure and complete," Etherplan, 11-May-2021. [Online]. Available: https://etherplan.com/2020/03/21/why-proof-of-work-based-nakamoto-consensus-is-secure-and-complete/10509/. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

E. Kim, "Bitcoin mining consumes 0.5% of all electricity used globally and 7 times Google's total usage, new report says," Business Insider, 06-Sep-2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.businessinsider.com/bitcoin-mining-electricity-usage-more-than-google-2021-9. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

"Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index." Digiconomist, 6 Nov. 2021, https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption/.

D. O'Mahony and S. Zhao, "Applying blockchain layer2 technology to mass E-Commerce," TARA, 01-Jan-1970. [Online]. Available: http://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/92481. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

_Visa Fact Sheet Visa_. 31 Mar. 2021, https://usa.visa.com/dam/VCOM/global/about-visa/documents/aboutvisafactsheet.pdf. P. Viswanath, "Lecture 17: Bootstrapping blockchains." [Online]. Available: https://courses.grainger.illinois.edu/ece598pv/sp2021/lectureslides2021/ECE_598_PV_course_notes17_v2.pdf. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

T. Ometoruwa, "Bitcoin cash: Large blocks are not a proper solution for achieving scalability," CryptoPotato, 14-Nov-2021. [Online]. Available: https://cryptopotato.com/bitcoin-cash-large-blocks-are-not-a-proper-solution-for-achieving-scalability. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

K. Shirriff, "Mining bitcoin with pencil and paper: 0.67 hashes per day," Mining Bitcoin with pencil and paper: 0.67 hashes per day. [Online]. Available: https://www.righto.com/2014/09/mining-bitcoin-with-pencil-and-paper.html. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].

J. Naughton, "Is blockchain the most important it invention of our age? John Naughton," The Guardian, 24-Jan-2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jan/24/blockchain-bitcoin-technology-most-important-tech-invention-of-our-age-sir-mark-walport. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2021].